CNN

—

When it comes to sport and social media, the English Premier League (EPL) and Facebook are at the top of their respective tables.

All EPL clubs have a presence on the social network where they post content and interact with fans. At one stage, Facebook even looked set to become an official EPL broadcast partner in Southeast Asia until a reported deal fell through last year.

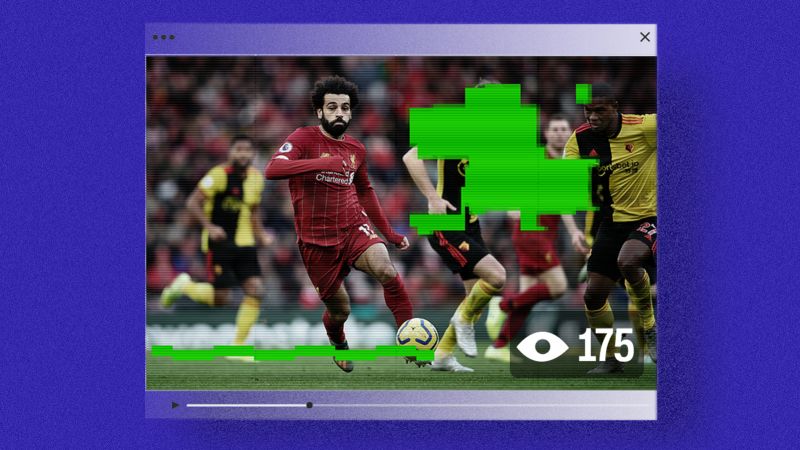

Yet pirated broadcasts of EPL matches have been visible on the social media platform this season – bypassing the Premier League’s multi-billion dollar TV rights model and raising questions about Facebook’s ability to police the content uploaded to its site.

CNN Sport has found more than 200 Facebook Live broadcasts in recent months showing EPL footage that appeared to be pirated from official rights holders who have forked out eye watering sums to show matches in their territories.

READ: ‘There could be a psychological cost’: How will footballers manage working from home?

One post CNN found, featuring Tottenham’s recent fixture with Manchester City, showed it was being watched by as many as 15,000 people before shutting down mid-match.

Another displayed a live broadcast of Arsenal’s February trip to Burnley that was emblazoned with the branding of beoutQ.

CNN could not say for certain whether the footage had been taken from beoutQ or its logo had been added by an individual uploader. BeoutQ has not responded to previous emailed requests for comment from CNN on its operations in recent months.

EPL broadcasts were found on YouTube and Periscope as well but these were isolated and far fewer than what could be found on Facebook.

A Facebook company spokesperson told CNN that it puts significant effort into preventing piracy and immediately acts on reports of pirate broadcasts.

A spokesperson for YouTube said it has invested heavily in copyright and content management tools and takes down matches when it finds them.

Periscope, which is owned by Twitter, did not provide on the record comment when approached by CNN.

According to a variety of experts CNN spoke to, illegal streaming sites and programmed set-top boxes likely still offer more prominent forms of piracy.

Gareth Tyson, a senior lecturer at Queen Mary University of London who has conducted research into the availability of pirated movies and TV series, was one who acknowledged as much. Yet Tyson added it was still “palpably” clear social media companies face a challenge with copyrighted content being uploaded onto their platforms.

The live videos CNN found, during selected match times between December and March, were just a sample of those posted with the sheer volume meaning it was not possible to track them all.

Most broadcasts CNN observed would stay live for between five and 10 minutes before shutting down. However, new posts would often immediately appear before being removed a few minutes later. This process would then repeat throughout the course of the most popular matches, many of which could be viewed in close to their entirety if viewers were willing to put up with the interruptions.

Some live videos CNN found offered longer coverage. The January EPL fixture between Bournemouth and Watford was effectively shown in full on one Facebook Live broadcast.

Others CNN observed showed live coverage for a short period before asking viewers to click on a link that would take them away from Facebook to continue watching.

Although matches could be viewed with relative ease, broadcasts often lagged behind the action while stream quality varied widely. The picture was flipped in some broadcasts while others had alternative audio or commentary.

Many streams appeared to be pirated from official broadcasters. Others appeared to be posted by users filming from inside stadiums or on televisions in their homes, bars or cafes.

Most accounts posting matches used generic names often featuring words such as soccer, online and live streaming. Others were named after the specific games being broadcast while a small number appeared to be posted from the personal accounts of individuals.

The videos CNN found were all posted publicly and did not include results from private Facebook groups.

Fans of EPL clubs have long complained over rising ticket prices and the cost of subscription packages to follow their favorite teams, perhaps offering reasons why some have looked for other ways to follow EPL matches.

In the UK, strict broadcasting laws remain in place that mean matches staged on Saturday afternoons cannot be broadcast live. This leaves many ticketless fans unable to watch unless they find a pirate broadcast.

While the issue of live sports streaming on Facebook has been raised in the UK press previously, little appears to have changed in the period since.

CNN asked the EPL as well as two anti-piracy firms that have worked with the league for figures comparing the volume of streaming on social media sites to other forms of piracy, but none were forthcoming.

One study last year claimed that illegal streaming saw EPL clubs lose out on £1 million ($1.3 million) per game in lost advertising and sponsorship revenues, although it was unclear if this figure included analysis of piracy on social media platforms.

For its part, Facebook engages with the likes of the EPL and says rights holders can report live videos at any time during a broadcast which it will then look to block or take down.

A Facebook company spokesperson told CNN that it devotes “significant resources to address and prevent piracy for videos” and has a team of over 35,000 people to help address copyright violations as well as automatic detection and reporting tools.

These tools include Rights Manager, which Facebook says allows football rights holders to report videos in real time as well as provide reference streams so offending content can be compared and easily identified. Facebook also utilizes Audible Magic, a platform that automatically blocks audio-visual uploads that match content listed in a database.

Kevin Plumb, EPL director of legal services, said that “unauthorized streaming of our content on any platform is illegal.” He added that the league works with social media companies to get the best out of the “automated filtering and takedown tools they have available to remove pirated content.”

Away from social media, the EPL has taken legal action to force major internet service providers in the UK to block and disrupt servers hosting illegal streams of its matches while three men found guilty of selling illegal streaming devices were sentenced to a combined 17-years in prison last March.

Matt Phillip, a senior associate at UK law firm Shepherd and Wedderburn with an expertise in sports law and intellectual property, says it has made sense for the EPL to target pirate sites and the suppliers of hardware that enables illegal streaming as these methods are now well understood by courts, in the UK at least, are reliable and have a greater overall impact than targeting social media streams.

The fact that social media sites engage with the copyright holders to remove streams can also create alternatives to legal redress, Phillip adds.

Yet even with reporting methods, tools and protocols in place, matches continue to appear and reappear suggesting these anti-piracy measures are not completely effective.

With more than two billion users, any one of whom is able to post a live video, the challenges of knowing precisely what is happening at all times is clear.

Facebook’s own rules state that posting copyrighted content is against its standards.

Experts CNN spoke to, however, highlighted how laws surrounding the broadcast of copyrighted material often lag behind what’s happening on a number of platforms.

In countries such as England, where the EPL is based, social media firms like Facebook are protected from liability when it comes to intellectual property infringement around user generated content if they are unaware of the infringing activity or if they remove it expeditiously once they disover it is there, says digital media lawyer with the London-based Sheridan’s firm, Jack Jones.

Bonnie Tiell, professor of sport management at Tiffin University in Ohio, says US legislation brings up its own challenges with the “burden to police infringement violations (falling) on the owner of copyrighted material” rather than the platforms hosting the content, she says.

Without a change in laws or social media companies rolling out tools that identify copyrighted content more quickly, Jones believes it likely the status quo where streams appear, are taken down and then reappear will likely to continue.

Yet he adds that new legislation to address the issue could be possible in the years to come.

Phillip broadly agrees and says the UK government’s recent response to an online harms white paper, while specifically targeting terrorist and child exploitation material, could see greater transparency on the topic of content removal.

This could “impact the way that social media platforms deal with other illegal content, such as illegal streaming and infringement of intellectual property rights,” he adds.

EPL clubs and their broadcast partners, at least, will hope for as much as they seek to stamp out pirate broadcasts of their products.