Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

CNN

—

In 1660, a ship carrying a treasure trove of luxury goods sank off the coast of Texel, the largest island in the North Sea.

Nearly four centuries later, little remained of the wooden unidentified Dutch merchant ship. But as the silt and sand covering the wreck washed away, broken chests began to appear in 2010. Four years later, divers retrieved the chests and brought them to the surface.

Inside were remarkable objects, the likes of which had never been seen before, according to researchers at the Museum Kaap Skil in the Netherlands, where the exclusive collection of items are on display.

The chests were full of clothing, textiles, silverware, leather book bindings and other goods that likely belonged to people from the highest social classes centuries ago.

Some of the most stunning items include two virtually intact lavish gowns — a silk dress and another one interwoven with pieces of silver that was likely a wedding dress. Few textiles or clothing from the 17th century remain preserved today, and it’s even more rare to find them in shipwrecks because fabric decays so quickly.

“When I saw the clothing for the first time, I must say, that I actually found it very emotional,” said Emmy de Groot, a textile restorer and adviser who studied the dresses, in a video shared by the museum. “Clothing is something so personal. And you’re holding something in your hands that has been worn on someone’s body. How close can you come to someone from the 17th century?”

The silver dress, revealed in November 2022, has joined an exhibition of items recovered from what is now known as the Palmwood Wreck at the Museum Kaap Skil.

The two gowns, both made of expensive silk, were found together in the same chest.

The first silk dress, originally revealed in 2016, looks like something that could be worn in a period drama rather than an item of clothing that laid on the seabed for nearly four centuries.

Made of silk satin damask, the garment has a woven floral pattern. The gown includes a bodice, ruffled sleeves and a full pleated skirt that fans open at the front, which is similar to Western European fashions between 1620 to 1630.

To complete the look, the gown would have had underskirts, sleeves that were likely adorned with silk tassels and silver or gold buttons, and a stand-up collar made of linen or lace, as well as other embellishments.

The dress includes cream, red and brown colors, but researchers believe it began as a single color. Over time, the original dyes dissolved, while staining from other garments in the same chest left their mark. Despite its intricate design and expensive fabric, the dress was likely intended for everyday wear.

The silver wedding dress, on the other hand, was made for a special occasion and was found in separate pieces, including a bodice and skirt. The dress features embroidered plaited patterns of silver thread that resemble knotted hearts, as well as actual silver disks sewn onto the dress.

“Thanks to the silver, the dress would have had a formal, light and sparkling appearance,” conservator Alec Ewing said.

“It must have been one of the most extraordinary dresses that a lady from the highest social classes in Western Europe would have worn in her life. Silver fades and deteriorates relatively fast in salty environments but the traces and patterns of the original decorations are still visible.”

The dress appears brown now, but it likely began as white, cream or yellow silk.

“It is unbelievable what we have discovered here, this is one of the most unique historical finds ever,” said Maarten van Bommel, exhibition researcher and professor of conservation science at the University of Amsterdam, in a statement. “There may only be two such dresses in the whole world. And they are both here, on Texel.”

The dresses were rinsed to remove excess salt, but very little conservation work was actually needed for either garment. In order to protect the dresses, which are laid out on display at the museum, they have been stored in special display cases filled with pressurized nitrogen, which removes all oxygen to prevent deterioration, Ewing said.

“Thanks to this solution, we expect to be able to display the dress and other treasures for a period of years without harm,” he said.

In the same chest as the gowns were knitted silk stockings, a robe, a red bodice and a woman’s toiletry set. Researchers were puzzled by the fact that none of the clothing is the same size, so it’s possible that the items belonged to a family that was traveling together, Ewing said.

The ship may have been transporting the items of an affluent family to another country, said Arent Vos, the museum’s senior archaeologist.

The velvet robe, which may have been a caftan, includes a jacket and short skirt — but torn edges suggest the two pieces were once connected. The robe may have come from the Ottoman Empire or Eastern Europe. The bright red dye, derived from insects, was one of the most exclusive dyes in the 17th century, according to the museum researchers.

The red brocade bodice, which remains preserved in excellent detail, would have been worn with sleeves over a skirt. Eyelets show where the bodice was once laced, and there are imprints from whalebone stiffeners that were used for shaping.

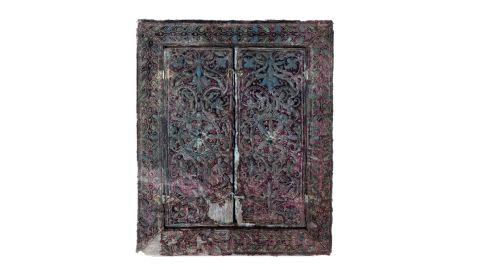

A delicate toiletry set includes a silk-covered brush, the remains of a pincushion, a comb and a table mirror with two doors that was covered in embellished silk velvet.

Adjacent chests included 32 gilded leather book bindings, including one bearing a stamp of the Scottish-English royal family Stuart’s coat of arms. The covers represent the remains of an expensive library, with book bindings from England, France, Germany, Netherlands and Poland made in the 16th and 17th centuries.

A silver cup, broken in three pieces, was also retrieved from the wreck site. The cup is similar in style to goblets made at the end of the 16th century in Nuremberg, Germany, where many silver goods were produced. The cup’s lid features Mars, the Roman god of war.

Divers also recovered an ebony cross-staff, or an instrument used for navigation and latitude on Dutch ships. The pieces show the initials of its craftsman, H.I., as well as the year 1626.

Hundreds of centuries-old shipwrecks lie along Texel’s eastern coastline, which is part of the Netherlands. The area, once known as the Texel Roads, was a central hub for ships to anchor that sailed on European trade routes.

More than a hundred ships could be anchored at the Roads at any given time in the 17th and 18th centuries. While the coast provided some protection from the elements, it couldn’t shelter the ships from powerful storms that released vessels from their anchors and crashed them into one another, or grounded them on sandbars.

The catastrophic storms sank between 500 and 1,000 ships before trade routes stopped using the Texel Roads in the second half of the 18th century. About 40 shipwrecks have been located since the 1970s, but for most of them, little remains.

Many of the ships disintegrated over time — but the shipwrecks immediately covered in mud and sediment experienced a slower rate of decay.

Divers first located the Palmwood Wreck in 2010 on the Burgzand, part of the Wadden Sea to the east of Texel. As sand continued to wash away from the wreck, it became exposed enough in the summer of 2014 that divers could retrieve artifacts from the wreck.

High-quality hardwood logs made from palm wood were found on the wreck’s top layer, likely representing the original deck of the ship — hence the name researchers have given the ship since it’s unlikely they’ll ever discover its identity.

Without a ship’s name, definitively attaching an owner’s name to the Palmwood items will be difficult, Ewing said. But the luxury goods tell their own story, revealing more about what life was like for the upper echelons of society in the 1600s.

And there are more stories waiting to be told.

“The waters surrounding Texel are littered with shipwrecks, and we expect that divers will always be on the lookout,” Ewing said. “These other wrecks, mostly Dutch merchant vessels from the 17th and 18th centuries, are invaluable treasure troves for learning more about history and heritage as well. We definitely expect that one or more new wrecks will be spotted over the coming year.”